|

The Satanic Screen Book review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

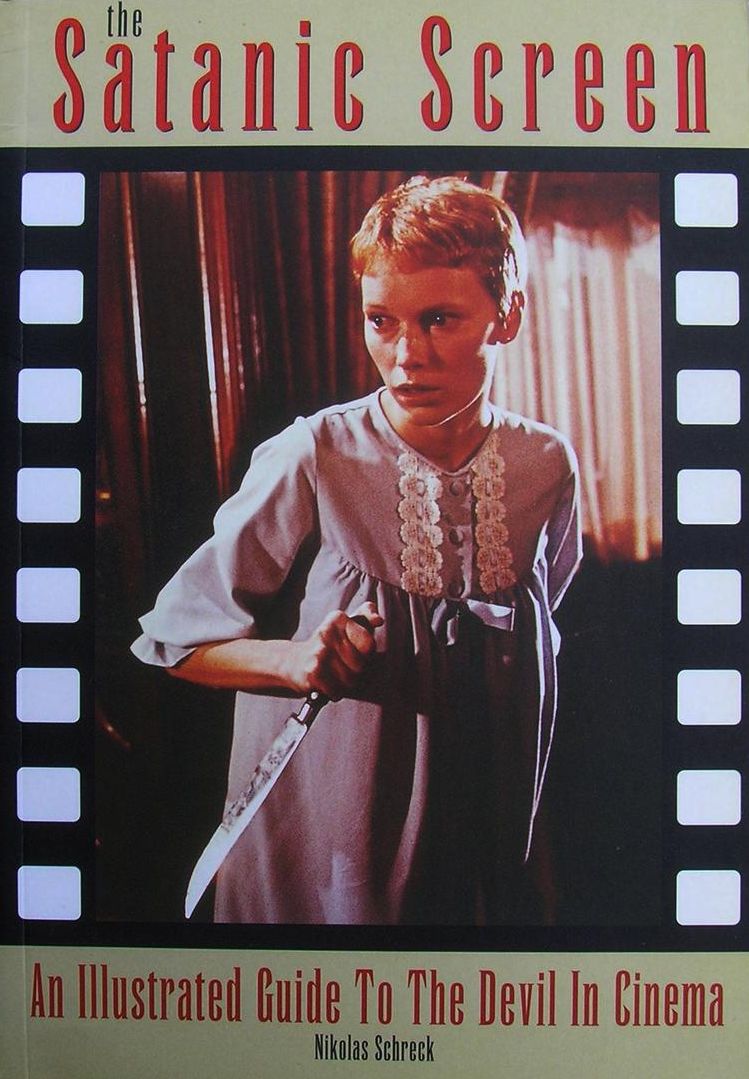

The Satanic Screen: An Illustrated Guide to the Devil in Cinema (by Nikolas Schreck, Creation Books, 2001, 256 pp.)

Schreck sets the tone in his opening sentence: "According to tradition, the Devil has always been a celebrated patron of the arts. Quite apart from the vague and somewhat contradictory references to his personage found in the Bible, Satan has maintained a long and distinguished presence in Western culture. Indeed, it is as a constantly shape-shifting entity of the creative imagination that Lucifer has been most enlivened in mankind's consciousness." Schreck begins with the 1600s, writing: "The history of the Satanic cinema truly begins with the magic lantern spectacles of the seventeenth century, which delighted and frightened pre-cinematic audiences with elaborate illusions of light and shadows." His first chapter examines this "pre-cinematic cinema," then follows a chapter on silent films, then one chapter for each decade from the 1930s through the 1990s. Schreck is knowledgeable if opinionated, not necessarily a bad quality in a critic (though some readers will be annoyed when he refers to "Judeao-Christian mythology" as a given). Yet his deeply-held perspective (sympathy for the devil as symbol of liberation) results in some thought-provoking critical analysis. Of 1950s indie filmmaker Kenneth Anger, Schreck writes: "Anger's vision of the Devil has nothing to do with the Christian figure of damnation. For him, Lucifer is the principle of light and liberation, and the mystical vision projected in his films is not so much traditionally Satanic as it is Luciferian." However, this critical strength is also a weakness, as it causes Schreck to seek meaning where there is none. In discussing the 1959 Mexican children's film, Santa Claus (wherein Santa combats Satan), Schreck writes: "Of course, the alert reader has already noticed the cryptic occult message hidden in this seemingly harmless family picture ... Santa as an anagram of Satan." Schreck doesn't elaborate on why this anagram is relevant to anything because, I think, it's not.

Still, Schreck is even-handed in his theological criticism. Aleister Crowley (inspiration for many horror novels and films, such as Dennis Wheatley's The Devil Rides Out) is presented warts and all. Likewise, Wiccans will bristle when they read Schreck's chapter on the 1960s, wherein he writes: "To the contemporary reader, whose idea of a witch may be influenced by the sweetness-and-light Wiccans who have appropriated the word, the dark aesthetic of the '60s witch must be emphasized. Seeing themselves as sisters of Satan, the majority of that era's witches were a far cry from the current Wiccan movement. Just as today's Wiccans are constantly pointing out indignantly that they are not Satanists, the witchcraft movement of the sixties reveled in its romantically diabolical associations." (It is noteworthy that while Wiccans insist that Satan is a Christian deity, the Church of Satan's website claims that Satan is just another name for the universal pre-Judeao-Christian concept of a dark deity -- a claim that mirrors the Wiccan concept of a universal pre-Judeao-Christian mother goddess.) But to his credit (and in contrast to his Santa Claus analysis), Schreck rarely lets his opinions interfere with his historical objectivity. Most of his book is necessarily devoted to horror films, and Schreck proves well-informed, having done much primary research. He not only covers film aesthetics -- and the films' production, distribution, and critical histories -- he examines the films in their broader occult context, relating events in the world of Satanism as these films were being made and seen. Schreck's research into Rosemary's Baby's production history -- and his critical analysis of Roman Polanski's aesthetic intent -- is especially impressive. Schreck investigates and disputes Satanist Anton Szandor LaVey's widely circulated claim of having played the part of the devil. (Satan was played by Clay Tanner).

However,

though Schreck provides an informed overview of LaVey's career,

I may have found a hole in Schreck's research.

Schreck writes: "In 1969, Anton LaVey was commissioned by paperback publisher Avon to put together a book designed to capture the growing occult market Rosemary's Baby had helped to spawn. Despite its paucity of content, and several allegedly plagiarized passages, the book established LaVey as the brand name of pop Satanism." Nevertheless, a successful author of many years tells me that The Satanic Bible was ghost-written by Mike Resnick. Another well-established editor confirmed to me many years ago "that was the rumor." (I've not queried Mike Resnick about the matter).

The Satanic

Screen is impressive in its research and coverage. Printed on

heavy gloss paper. Nearly 150 black & white illustrations.

Same high-quality printing as in past Creation Books.  Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).

Nikolas

Schreck writes that centuries of artists have had sympathy

Nikolas

Schreck writes that centuries of artists have had sympathy