|

Lost Souls Film review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

Lost Souls (2000, dir: Janusz Kaminksi; scp: Pierce Gardner, Betsy Stahl; cast: Winona Ryder, Ben Chaplin, Philip Baker Hall, Ashley Edner, John Hurt. W. Earl Brown)

How about "coming of the Antichrist/Armageddon" films? Can't get enough of those? Even wanna see an Antichrist film featuring the visuals of a dotcom commercial? Now's your chance! This is no putdown. Storywise and stylistically, Lost Souls breathes new vibrant life into Revelations. No mean feat, considering the oh-so-many times horror (and other genres) have retold the familiar tale of the End Of Times. Lost Souls retells the Revelation mythos from the perspective of a reluctant Antichrist. Peter Kelso (Ben Chaplin) is an atheist and best-selling author, slowly convinced by Maya (Winona Ryder) that on his 33rd birthday his body will be "taken over" by Satan. At which moment Peter will "cease to exist." (This slow self- awareness of one's own divine mission mirrors that of Christ in The Last Temptation of Christ -- although, in this case, Peter will no longer be "Peter.") Online discussion indicates that horror fandom's opinion of Lost Souls is sharply divided. The controversy includes the story (especially its "small" ending), but is primarily directed at the film's visuals. Regarding the story: One fan praised the film for its provocative questioning of the nature of religion, God, and Satan. I disagree that it does that, although I join the film's admirers. Lost Souls's perspective is intriguing, but not subversive. Its fundamental story is rigidly faithful to Revelation. God is all-good and all-powerful. Satan is evil, the Great Deceiver. Man (or woman, i.e., Maya) can defeat Satan with sufficient Faith in Christ. About that "small" ending. Many viewers have a problem with it. How does one end an Antichrist film? If one's expectations derive from The Omen series, The Omega Code, The Devil's Advocate, The Seventh Sign, or The Visitor, one may expect impending Armageddon. Thunder and lightning, natural disasters and military battles, eardrum-shattering music and sound effects, even melting faces and flocks of doves. But director Janusz Kaminski thwarts our expectations. His ending is unexpectedly "small." A rising buildup to ... an abrupt whimper, not a bang. As the credits roll, you wonder: That's it? That's the end? And yet ...

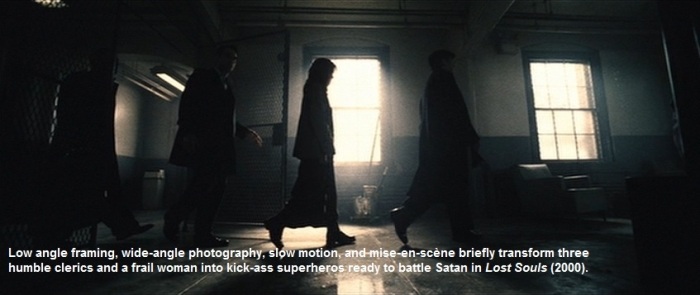

Give it time. It'll linger in your thoughts, and grow. An ending that's dark and moody and somber, one that you'll still be contemplating the next day. More so than when you saw it. Warning: Don't return the video immediately after viewing it. Not unless you must. You'll want to see Lost Souls again, the very next day. Second warning: Lost Souls is best seen alone, in the dark. I, unfortunately, saw it with a friend. She kept interrupting, asking questions, making comments. Lost Souls has atmosphere, pace, rhythm. A bright room with loud viewers will dampen its impact. And although it has an extremely well-structured script (I saw some things coming, which is not bad), it's not a simple script. If you don't pay attention, you'll soon find the succession of events confusing. About its atmosphere. The controversy over Lost Souls pertains less to its story than to its style, which threatens (but does not) overwhelm the story. Although Lost Souls is Kaminksi's directorial debut, he's long been a leading cinematographer (his credits include any number of Spielberg films, including Saving Private Ryan and Schindler's List). Some critics contend that Kaminksi has gone overboard in displaying his visual tricks. The film has the look of a TV commercial. White flashes punctuated by thunder, movements jarringly sped up (as though shot on video and transferred to film), a sepia-saturated world of grays, browns, and golds. A world simultaneously bright yet murky. Cold and pale. The metallic look of The Matrix, or a Wired magazine ad, or a dotcom commercial. Here's an example of Lost Souls's hyper-stylization: Early in the film, three priests (one, the elderly John Hurt) and Maya enter an asylum to perform an exorcism. They stride single file, slow-motion, their long steps exaggerated with a wide-angle lens, their loose clothes billowing (reminiscent of The Matrix's trenchcoats), their feet thundering with every step. (See below.) Appearing as four futuristic tough-guys approaching a duel; yet this curious mise-en-scene is here applied to three physically unimpressive priests, and one slight, frazzled woman.

This contrast between style and content risks satire; yet Kaminski intends no satire, and to his credit, we're not laughing. Equally visually stunning is a late scene, shot in telephoto: an SUV driving under a bridge, under the fiery semicircular rings of ... some sort of Men-At-Work light fixtures, a looming electronic sign reading: No Access. Do these stylistics serve an aesthetic purpose? One can find one. Kaminski's dark, somber cinematography creates the impression of a world under a cloud (it's often raining), of an impending doom descending on humanity. The characters' jarring motions adumbrate the metaphysical and ethical disintegrations inherent in Armageddon. The thundering footsteps shot in slow motion emphasize the import of the impending confrontation. And of course, the impressive stylistics and special effects build to provide that much more contrast with the unexpectedly "small" ending. So yes, one can aesthetically justify Kaminski's stylistics. But one is also tempted to wonder: Are these justifications the real reason for his stylistics, or did Kaminski apply them simply because they looked cool? Certainly, the film's detractors think so. Yet, Kaminksi's stylistics work for me. And although they threaten to overwhelm the story, they do not do so. Especially when Kaminski mutes the stylistics near the end, shifting emphasis to the story. Normally, horror works best on a low-budget; Lost Souls is an example of a big budget put to good use. A low budget couldn't deliver Kaminski's visuals. Despite its stylistics and controversy, Lost Souls's story and structure is traditional. Maya and her priestly allies have determined that Peter is the coming Antichrist, and they must stop him. Either by working with him, or if need be, against him. Contrast that with a nontraditional (and smallish) Antichrist film: Hal Hartley's The Book of Life (1998). Unlike Lost Souls, The Book of Life is not a horror film, not even a horror-art film. It's an indie film that bears some striking similarities to (and striking differences from) Lost Souls. Like Lost Souls, The Book of Life features nontraditional stylistics. Shot on digital video, The Book of Life features pale impressionistic visuals, and skewed camera angles. Storywise, it too features a reluctant Antichrist. But unlike Lost Souls, The Book of Life also has a reluctant Jesus. God is the heavy, distant and cruel, because He seeks to destroy Earth through Armageddon. Jesus wishes to avert Armageddon, for humanity's sake. The Antichrist shares Jesus' goals, preferring to keep things just as they are. Together, Christ and Antichrist plot to subvert God's plans for Armageddon. Lost Souls proffers no such theological ambivalence. Maya is wholly committed to God, her Faith strong. Through Faith in her Catholicism, she is able to ferret out Satan, recognizing his lies in the possession of a priest.

Surprisingly, Meg Ryan is credited as one of Lost Souls's producers. She does not appear in the film, so it seems she's a genuine producer here, rather than an actress using her clout to assume the title. With Lost Souls, Ryan has reason to be proud. I predict that Lost Souls will be the Blade Runner of horror. Blade Runner was a critical and box office bomb upon release, condemned for its "style over substance," yet slowly it built a cult following, becoming one of the most admired and influential science fiction films in history. Lost Souls is the finest horror film of 2000, so naturally, the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films didn't even nominate it for their annual Saturn Awards. Here are the Academy's nominations for the year's Best Horror Film: Dracula 2000, Final Destination, The Gift, Requiem for a Dream (sic!), Urban Legends: Final Cut, What Lies Beneath (barf!). That's right. An Urban Legends sequel is a nominee, Lost Souls is not. (If you're looking for The Cell or The Hollow Man, they were nominated for Best Science Fiction Film, although they could be considered horror, so go figure.) Considering its past roster of nominees and winners, a snub from the Academy is probably the best assurance you could have on the excellence of Lost Souls. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).

You like

those dotcom commercials? The ones with sped up herky-jerky motion,

and cool electro-bright colors? Or those Mercedes-Benz TV ads, with

the sudden flashes of white intercutting sepia-toned shots of cars careening

amidst a starkly cold environment?

You like

those dotcom commercials? The ones with sped up herky-jerky motion,

and cool electro-bright colors? Or those Mercedes-Benz TV ads, with

the sudden flashes of white intercutting sepia-toned shots of cars careening

amidst a starkly cold environment?