|

The Jar Film review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

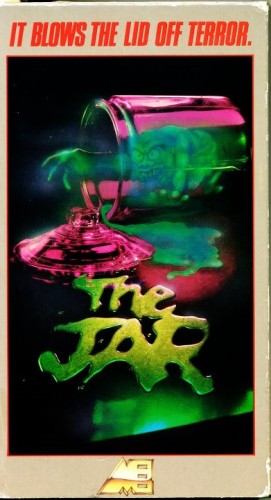

The Jar (1984, dir: Bruce Tuscano; cast: Gary Wallace, Karen Sjoberg, aka Carrion)

I've discussed The Jar in Midnight Marquee, in my horror collection, Halloween Candy, and in my Horror Film Aesthetics. I do so again because the film remains obscure and out-of-print, whereas it deserves to be celebrated and reissued. (The Jar was briefly released on video by Magnum in 1987, and old copies occasionally surface on Ebay). Granted, some critics contend The Jar's obscurity is well-earned; that under the rough there's only ... more rough. John Stanley writes: "For 90 minutes little happens while Gary Wallace sits and looks either blank or frightened. ... an auto accident [is] filmed so darkly one can barely see it ... very few visuals ... isn't worth one's time." Au contraire. The Jar is an engrossing indie gem, and a quintessential example of pragmatic aesthetics. By pragmatic aesthetics (Chapter 2 in my Horror Film Aesthetics), I mean that a filmmaker has applied budgetary compromises to aesthetic effect. Forced by a low budget to compromise on location, lighting, whatever, the filmmaker has used that limitation in a way that enhances the theme or story. Okay, so what's The Jar about? The Jar is a surrealistic horror art film about an unassuming young man (Paul, played by Gary Wallace) who chances upon a jar containing a pickled demon-thing. After his dark discovery, the film chronicles Paul's progressive mental deterioration as he struggles to understand and overcome the demon's creeping psychic encroachment. Paul is tormented by surreal visions: Blood arises in his bathtub and a boy emerges from the blood; water drips in a grotto; a restaurant wall transmutes into a doorway of glowing pebbles; children ride a merry-go-round; a youth kills a boy in a foggy urban park and escapes with Paul; black-robed monks trudge toward a crucifixion in the desert; during a hairy Vietnam battle, a tuxedoed yuppie sipping wine observes Paul's neighbor landing in a helicopter to rescue him. And Stanley claims The Jar has "very few visuals"? Sic! The visuals are not only numerous, but incorporate impressive locations too. And yet despite their wide-ranging diversity, the locations and visuals support The Jar's surreal conceit. Securing appropriate locations is a major concern for low-budget filmmakers. Studios cost money, and the filmmaker's apartment can rarely double up for every indoor scene in the script. Outdoor locations are a practical solution. Nature's inexpensive majesty is equally impressive whatever a film's budget (hence, the many summer camp slasher films). Director Bruce Tuscano makes sweeping and imaginative use of The Jar's many outdoor locations, setting elements of his story in a Colorado desert, a Vietnam battlefield (albeit a distinctly non-tropical one), an urban park. Taking full advantage of his locales, Tuscano pans across the widely-spaced monks in the desert, then tracks the American platoon's trek along a Vietnam river. Naturally, Tuscano reverts to a tight frame when he must hide his less impressive (or nonexistent) locations in offscreen space.

About Tuscano's tight framing: The Jar begins with an auto accident involving Paul and a strange old man (who resembles Phantasm's Angus Scrimm). Closeups of stationary car lights are all we see of the "accident." Tuscano's frame follows Paul leading the old man into Paul's car, but Tuscano does not show us the accident wreckage, or other cars on the road, or even the road itself. Tightly framed and darkly lit, Paul's car might simply be sitting in Tuscano's driveway as Paul "drives" down the highway, a garden hose showering the windshield to fabricate rain. (Later, Paul "runs" in the rain, possibly in the middle of the highway. Surrounded by darkness and a tight frame, he appears to be running in place -- as he most probably is -- possibly in Tuscano's backyard.) Yes, Stanley is correct in that the accident is darkly lit. But this is to Tuscano's credit. He effectively uses low lighting and tight framing to (pragmatically) hide a nonexistent accident. But these pragmatic choices also enhance The Jar's surrealism. Hence, a pragmatic choice works aesthetically. Editing is rough. Paul smiles blissfully, we jump cut to a radically different angle, same scene, and now he's no longer smiling. Other jump cuts leave story elements missing, as though we've skipped over a plot point. Jump cuts are underscored by subtle changes in lighting and color hues from shot to shot, within the same scene. It's as if Tuscano used different film stocks within the same scene, or shot on different days and was unable to recreate the previous day's lighting setup. Rough editing may be expected on a low budget. Seamless editing is expensive. To ensure a final edit without jump cuts, a director will often film several master shots from different angles, followed by medium shots, closeups, and insert shots of that same scene. Low-budget filmmakers may attempt to save on film stock by only shooting the necessary minimum of footage. If they foresee using a closeup in the final edit, they will forego a master shot which might have ensured a smooth transition.

Likewise, while big budget directors avoid using different film stocks within the same film (excepting a specific aesthetic motivation, as in Natural Born Killers), low-budget filmmakers often have no choice. Film stock is costly, and money can be saved by buying "short ends" and recans. Money is also saved by using film stock donated by studios, manufacturers, labs, cooperatives, and arts councils. Often, a low-budget filmmaker uses whatever he or she gets, making do with film stocks of different ASA from different manufacturers. Hence, the differing color hues within the same film. But while Tuscano may have had no choice, The Jar's rough production values aesthetically support the story's surrealism. Paul is battling demonic possession and its concomitant mental breakdown. He laments to Crystal (Karen Sjoberg), his neighbor and nascent girlfriend, that he no longer knows what's real, what's imagined. This deterioration of his subjective reality is effectively conveyed by his (dis)placement in expressionistic locales, and by the jump cuts and changing color hues. The Jar's rough soundtrack further enhances its surrealistic aesthetics. The Jar seems to have been shot MOS (without synched sound), with the dialogue dubbed in afterwards. Also, the scenes contain no ambient sound. MOS filming saves on labor and sound equipment, and is often used by Hollywood filmmakers when a scene contains no dialogue. But only very low-budget filmmakers shoot scenes containing dialogue MOS, and even then, they mix in ambient sound, if only from another source. Yet not only did Tuscano appear to shoot The Jar MOS, he avoided mixing in ambient sound from any sources.

This lack of ambient sound imparts a disembodied background silence to The Jar, as though we were listening to the actors at high altitude, our ears congested. And although the dubbing is respectable, it's rough enough so that the unsynchronized voices, conjoined with the disembodied silence, support Paul's slow disassociation from reality. Paul's conversations with Crystal and Jack (his boss) resonate with Pink Floyd's line: "Your lips move but I cannot hear what you're saying." Paul hears what they're saying, but the subtle vocal desynchronization creates an impression that the fabric of his universe is disintegrating. As indeed it is. The Jar's soundtrack evokes Carnival of Souls (1962), a film whose imprecise sound synchronization reinforced its story about a soul trapped in an imprecise twilight world, one in which material reality was always on the verge of slipping away. Yet while Carnival of Souls filled its silences with eerie organ music, The Jar compensates with discordant sound effects (unearthly breathing, wheezing, and whining), a technique used to greater extent, and greater effect, in David Lynch's Eraserhead (1978). Comparisons to Lynch are apposite. As with Eraserhead, Tuscano's images only appear arbitrary. A water motif predominates: Paul running in the rain, taking a shower, blood filling a bathtub, the dripping grotto, the water from the waiter, spilled liquid from the broken jar, even the parched desert. Water often connotes sex, and Paul is conflicted over Crystal, whom he desires but spurns. As with Eraserhead, The Jar reveals a fascination with texture. Extreme closeups of Paul's faucet and drain are synched to unearthly reverberations. Extreme closeups transmogrify Jack's cigarette into an orange glow burning in an incongruous black void. For further emphasis, his one act of cigarette-lighting is depicted repeatedly, as is Paul's jar-smashing, thus evoking Battleship Potemkin (Soviet 1925). Also apposite, because Eisenstein too was a low-budget filmmaker; Soviet montage was developed in response to a shortage of film stock, necessitating creative editing of whatever stock footage was available. Fewer excuses can be made for Tuscano's occasionally out of focus shots, as when Crystal enters Paul's apartment and the camera tries desperately to bring her into focus. Most likely Tuscano simply couldn't afford a retake. Yet even these blurry images contribute to The Jar's surreal sensibility. Because it is Paul's POV on Crystal that is out of focus, this further suggests his weakening grip on reality. Colored lights are an inexpensive way to enhance an impoverished film. Tuscano makes heavy use of colored lighting, toward two aesthetic effects, both functionally consistent with his story's conceit: (1) As Dario Argento did in Suspiria (Italian 1976), Tuscano uses colored lights to suggest the presence of an evil entity. Paul looks in a mirror and sees the old man, lit in blue from a low angle. Then when Jack knocks on Paul's door, a quick flash of blue light from under Jack's chin intimates that Jack is now targeted by the demon; (2) As in Norman J. Warren's Terror (British 1978), much of Tuscano's colored lighting is nondiegetic (i.e., the lighting originates from outside the story). As Paul drives the old man away from the accident, Paul is lit from below in yellow-green, the old man in red-orange. As in Terror, these nondiegetic colored lights contribute a stylish sheen to The Jar's unpolished production values. But more importantly, they support The Jar's surrealism and Paul's mental deterioration. Stanley is correct in implying that The Jar's story is simple. A surrealist depiction of a man's mental breakdown. None of the frenetic action of Evil Dead or Re-Animator. As with Pulp Fiction (1994) or Eraserhead, The Jar eschews conventional narrative form. But The Jar is enjoyable on its own terms. And upon repeated viewing, one only grows to appreciate its artistry. The end credits reveal that The Jar even received some sort of Colorado arts council grant, but don't let that deter you from seeking out this gem. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).

Here's

an obscure diamond in the rough.

Here's

an obscure diamond in the rough.