|

Hollow Man Film review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

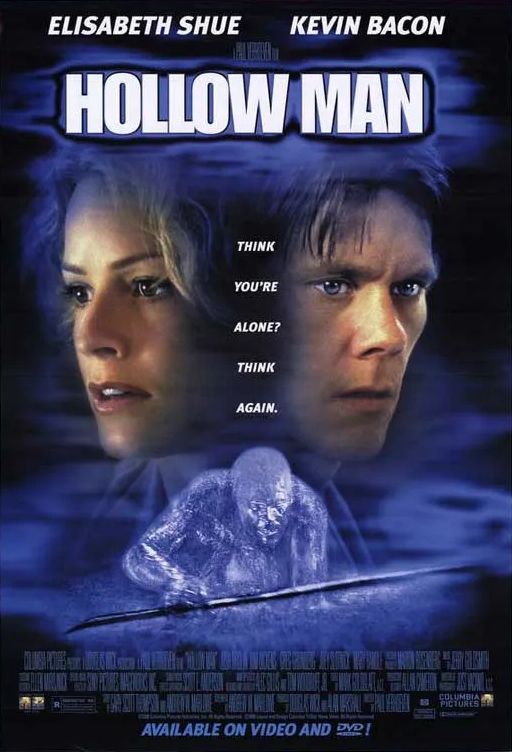

Hollow Man (2000, dir: Paul Verhoeven; cast: Kevin Bacon, Elizabeth Shue, Josh Brolin, William Devane)

Coincidence? Hollow Man has been nominated for a Best Science Fiction Film Saturn by the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, but it could just as easily have been nominated for Best Horror Film. Not because it's such a great horror film, but because it's more horror than sci-fi. There's not much of a plot. Kevin Bacon plays a brilliant young scientist heading a top secret military project in an underground lab near Washington, DC. His team includes Elizabeth Shue (his former lover), Josh Brolin (secretly bedding his former lover), and several bodies ... ehr, other young scientists. They've already turned several animals invisible. The difficulty lies in bringing them back to visibility -- alive. The story opens as they finally manage to do just that, with an ape. Bacon announces that they're ready to take the experiment "to the next level." Experimenting on a human. It's dangerous. The ape nearly died in the attempt to restore its visibility. Shue and Brolin oppose Bacon's recklessness. But Bacon is the gonzo genius (as he keeps reminding everyone), so it's settled. Without informing their military sponsors, Bacon's team injects the invisibility serum into him. As his flesh fades, his personality is revealed. Always conceited, blatantly comparing himself to God (this is not a subtle film), Bacon is liberated from human society's rules and expectations. He teases his teammates, playing voyeuristic games in the rest rooms with one woman, fondling another's breasts as she sleeps. Several days later, the team discovers that what worked with apes won't work on humans. Bacon's visibility cannot be restored. At least not yet. The team insists that Bacon stay underground while they seek a cure. Bacon grows frustrated. He does not like being treated like a lab rat. He does not like being ordered about by his underlings. He grows embittered, paranoid, jealous of his teammates. Antsy, he sneaks in and out of the underground lab. Outside, he discovers that invisibility confers ... power.

Bacon assaults his neighbor (possibly raping her; it's not clear). When he discovers Shue with Brolin readying for love at Shue's apartment, Bacon's jealousy and fury increase (as in The Invisible Man). Once everyone is back in the underground lab, Bacon cuts off all means of communication, seals all exits ... and body count mounts! That's what riled so many critics. What began as a sci-fi thriller with human drama, now morphs into a yet another slice & dice horror film, with Bacon determined to kill his entire team. It's not a bad body-count film. Until the killings start, we're treated to some cool invisibility special effects. And once they're underway, the killings are violent, visceral, and mildly imaginative. But while exciting, Hollow Man is not as suspenseful as it might have been. An invisible killer stalking his prey has much suspense potential. The Invisible Man delivered on that potential. But in Hollow Man, the gore and effects overwhelm any suspense. It's a cartoony sort of gore, the kind seen in martial arts films. There's no mention that the serum conferred any superhuman strength, yet Bacon withstands brutal physical abuse (at one point he's set afire with a flame thrower), yet he still returns for more killing. Much like Michael Myers and Jason Voorhees. And not only Bacon. At one point, Bacon slams Shue's head full force against a steel pipe. Her head bounces back, a large gash along her forehead. It's the sort of thing that may easily kill a person; at the very least cause severe brain damage. But Shue just arises from the floor, and they two continue pulverizing one another. The gore and destruction are exciting to behold, but insanely implausible. Shue, Brolin, and Bacon (scientists, not combat soldiers) battle inside an elevator shaft, an elevator rocketing past them, then plummeting back down, crashing against the walls, explosions shooting huge fireballs up the shaft.... Violence and mayhem as thrilling as in any James Bond film. And just as likely.

No, Hollow Man is not Arthur C. Clarke. It's not even Gattaca. It's not really science fiction at all. It's horror. As in Alien and The X-Files and Frankenstein, the "science" is mere window-dressing. Bacon's character is no scientist. He's a mad scientist. One of horror's progeny. One of ours. Hollywood likes young, attractive characters, thus, its sci-fi films normally feature brilliant, accomplished scientists too young to be so accomplished. Hollow Man follows that formula. Bacon and his team look like attractive Gen-Xers. In reality, both Bacon and Shue are nearly forty, but as neither looks it, the film (if not the story) capitalizes on their youth appeal. Hollow Man is a stupid film. Really stupid. And long, running at nearly two hours. Much of its potential for suspense was wasted. So too its potential to explore character, the extent to which self-identity stems from what we, and others, see of ourselves. Bacon could have made for an interesting mad scientist. Instead, watching the film, one often feels compelled to shout: "No way!" and "Get out!" If you're the sort who was satisfied with Twister because of its cool tornado effects, you'll likely be satisfied with Hollow Man because of its cool invisibility effects. And once the novelty wears off, you'll be treated to a generous and graphic body count, plus extensive scenes of laboratory destruction, and many explosions. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).

Invisibility

is a dangerous thing. In James Whales's

Invisibility

is a dangerous thing. In James Whales's