|

The Grand Guignol Book review by Thomas M. Sipos |

|

MENU Books Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Pursuits

Blogs Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

|

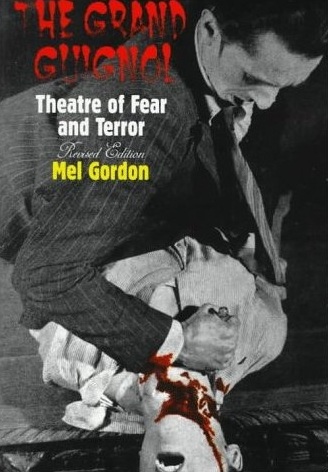

The Grand Guignol: Theatre of Fear and Terror, by Mel Gordon (De Capo Press, 1997 Revised Edition, 174 pages; trade paperback; US: $13.95, Canada: $18.50)

Gordon's Grand Guignol was first released in 1988. As this 1997 revised edition comes out four years after Skal's book, one wishes that Gordon would either have corrected his book or corrected Skal. But the discrepancy is unaddressed. Although Skal himself cites Gordon as a "Grand Guignol historian," Gordon's book provides only a sketchy history; 34 pages replete with illustrations (photos, newspaper cartoons, theater posters) supplanting text. We learn some interesting factoids. Despite its influence on filmic splatter, theatrical gore existed millennia before the Guignol's 1897 opening. Prehistoric shamans performed public self-mutilation. Ancient Egyptians and pre-Columbian Amerinds practiced ritual human and animal sacrifice, real and symbolic. Medieval Europeans used animal organs and limbs as stage props for human gore. During France's Reign of Terror "freshly-guillotined corpses were manipulated like oversized puppets in grotesque comedies." Grand Guignol itself means Big Puppet. Many influences shaped the Guignol's gory stage realism. By the 1810s, melodramas about and for the working class -- vulgar plays with broadly drawn evil rich oppressing the noble poor -- opened in Paris at a rate of seventy a month. Happy endings were mandatory, making these the Harlequin romances of their day. The Guignol's vulgar melodramas would drop that part. Faits divers, one-sheet news reports on grisly crimes, were another influence. Guignol playwrights often dramatized current crimes, a motif nearer to today's "true crime" genre than to horror. Edgar Allen Poe inspired a generation of French writers. So too Naturalism, an aesthetic movement exhorting a "scientific" theater. Naturalists insisted that art, in depicting people, must incorporate the latest findings in genetics, psychology, and environment. This was the century of Darwin, Freud, and Weber, and art eagerly embraced science. Stalislavsky's Method was one result.

Guignol founder Oscar Méténier had a morbid interest in science. He "scoured Paris's menacing red-light and working-class slum districts for over six years in a scientific search for naturalist material." Pre-Guignol he wrote for Théâtre Libre, using "real criminal types to play themselves in minor parts." His research enabled him to write authentic dialogue for "lowlife play figures, many of whom were based on real persons, and he found their instinctive and savage actions superior to the vain pretensions of Paris's bourgeois theatre-goers." A paradox emerges, perverse and peculiarly French. The Guignol espoused a creed exploding bourgeois taboos, pretensions, and hypocrisies, and of producing plays aimed at offending middle and upper class authority, manners, and sensibilities. Yet for all that, the Guignol was a mostly bourgeois and blue blood happening. Méténier, a journalist and police bureaucrat who enjoyed watching private state executions, needed to visit red-light districts in order to study the underclass. André de Lorde, perhaps the Guignol's most celebrated and prolific playwright, was a physician's son. His writing partner, Dr. Alfred Binet of the Sorbonne, was also his therapist. The audience included society's crème de la crème. Millionaires and aristocrats were regulars. "For premieres, audiences often attended in evening dresses and tuxedos, bringing their own champagne and glasses." Much of this societal success was owing to Max Maurey, an entrepreneur/showman who bought the Guignol from Méténier in 1898 and ran it till 1915. Maurey's ethos resembled P.T. Barnum more then Naturalist guru Emile Zola, supplanting a scientific theatre with pure theater, "where every social taboo of good taste was cracked and shattered." Maurey spread reports of patrons fainting from shock. Later Guignol producers advertised the hiring of in-house physicians, presaging William Castle.

As the Guignol was a world renowned tourist attraction by 1910, recommended in Parisian guidebooks of every language, its patrons evoke the armchair revolutionaries of later decades. Not surprisingly, after the Guignol's novelty wore off in the 1930s, its remaining patrons were largely French university students necking in the balconies. And American tourists. But however hot the Grand Guignol was with the flapper crowd in its heyday, it attracted others. One avid regular was Vietnamese refugee, and noodle and pastry cook, Ho Chi Minh. Hermann Goering was a loyal fan during the occupation. George Patton visited after liberation. Gordon's Conclusion asks: why study the Grand Guignol? His answer: censorship is a growing issue in art. He chides "otherwise liberal" people who favor government censorship if it suppresses gratuitous violence. He is being disingenuous. Apart from his brief Conclusion, Gordon rarely discusses censorship. When he does raise the issue, he makes a good point. "Théâtre Libre was under immense pressure to rid itself of both the naturalist mystery play and social documentary. Only because the Théâtre Libre ran itself as a private enterprise limited to individual subscribers were local censors held at bay." Gordon later adds that Méténier's "In the Family" was banned from public theaters. But after Gordon relates these instances of government arts funding leading to arts censorship, he immediately drops the issue. Elsewhere, he relates that Britain's SPCA tried to close its own Guignol (yes, there were foreign copies), fearing (wrongly) that wolfhounds were mistreated. But when Gordon says that the Italian Guignol "performed uninterrupted from 1923 to 1928," he doesn't state whether it closed due to a declining audience or to Fascist censors. If the latter, he doesn't explain why Mussolini permitted its uninterrupted five year run. Gordon never broaches censorship under Mussolini. Maybe it didn't exist? Or more likely, Gordon grafted the censorship issue on to the end of his book in a lame attempt at closure. The bulk of the book is composed of 100 synopses of Guignol plays, with author and year of première. Also included is André‚ de Lorde's essay "Fear In Literature" and two complete plays, one by de Lorde and one by de Lorde & Binet, translated into English. Not included is an index. Despite Gordon's cursory history of the Guignol and a particularly superficial look at the Guignol's influence on film, his book's extensive illustrations, synopses, and plays provide a decent introduction to this chapter in splatter history. Review copyright by Thomas M. Sipos

|

"Communist Vampires" and "CommunistVampires.com" trademarks are currently unregistered, but pending registration upon need for protection against improper use. The idea of marketing these terms as a commodity is a protected idea under the Lanham Act. 15 U.S.C. s 1114(1) (1994) (defining a trademark infringement claim when the plaintiff has a registered mark); 15 U.S.C. s 1125(a) (1994) (defining an action for unfair competition in the context of trademark infringement when the plaintiff holds an unregistered mark).

Does the

Grand Guignol still exist? Theater Professor Mel Gordon writes that

the celebrated French theater of splatter was demolished "in March 1963,

[when] with much fanfare, the building that housed the Grand Guignol was

totally destroyed." His account is detailed and colorful. But

in

Does the

Grand Guignol still exist? Theater Professor Mel Gordon writes that

the celebrated French theater of splatter was demolished "in March 1963,

[when] with much fanfare, the building that housed the Grand Guignol was

totally destroyed." His account is detailed and colorful. But

in