|

MENU

Home

Books

Horror Film Aesthetics

Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Vampire

Nation

Pentagon Possessed

Cost of Freedom

Manhattan

Sharks

Halloween

Candy

Hollywood

Witches

Short Works

Pursuits

Actor

Film Festival Director

Editorial Services

Media

Appearances

Horror Film Reviews

Blogs

Horror Film Aesthetics

Communist Vampires

Horror Film Festivals and Awards

Other

Business

Satire

Nicolae Ceausescu

Commuist Vampires

Stalinist Zombies

L'Internationale Song

Links

|

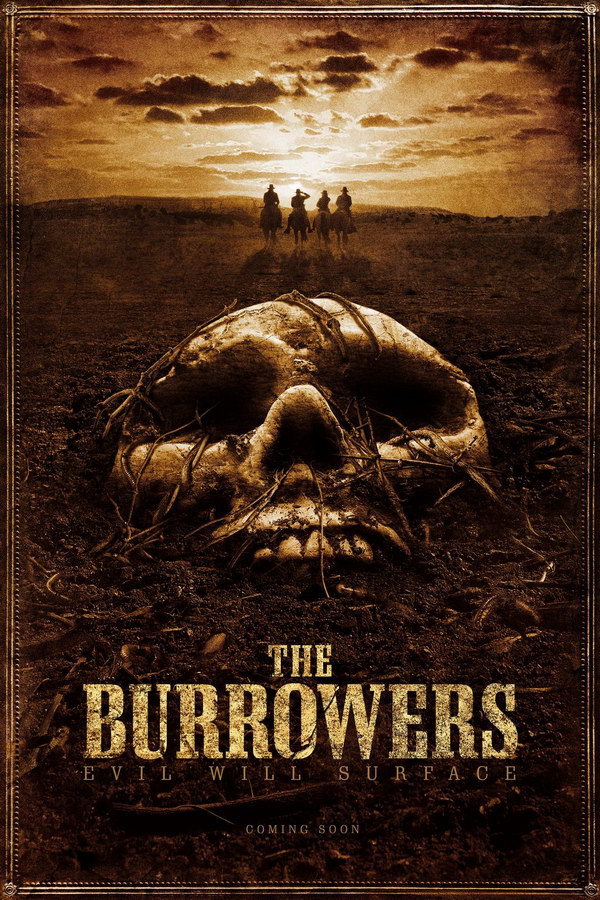

The Burrowers (2008, director:

J.T. Petty; script:

J.T. Petty;

cast: Clancy Brown, David Busse, Harley Coriz)

The “horror western” is a subgenre of the horror genre, not

the Western. The horror western uses Western icons

(e.g.,

Grim Prairie Tales), but its story conventions and

atmosphere are horror. It is marketed toward -- and attracts

-- horror fans, not Western fans. The “horror western” is a subgenre of the horror genre, not

the Western. The horror western uses Western icons

(e.g.,

Grim Prairie Tales), but its story conventions and

atmosphere are horror. It is marketed toward -- and attracts

-- horror fans, not Western fans.

Horror westerns normally mix these two genres from the

start. We see the Western icons (the period locale, cowboys,

Indians. etc.), but the story is soon, and clearly, horror.

The Burrowers is set in the Dakota Territories, 1879. But

rather than blend the Western and horror genres,

The Burrowers's strength is that it begins largely as

an authentic Western. Only after the audience is emotionally

adjusted to a Western does

The Burrowers become a horror film.

The Burrowers opens on a romantic conversation, set on an

idyllic Western ranch, a golden sunset in the background.

Coffey with Maryanne, as they discuss how he will ask her

father for her hand in marriage.

Minutes later, the first violent outbreak is typical of

Westerns -- we hear gunfire outside the cabin. The family

escapes to a cellar. They hear strange noises -- our

first hint of an

unnatural threat, as required by horror -- but we don't

see any

unnatural threats.

The family is killed. Maryanne is apparently kidnapped by

Indians. (Audiences know it wasn't Indians -- but are lulled

into believing that Maryanne may still be alive.)

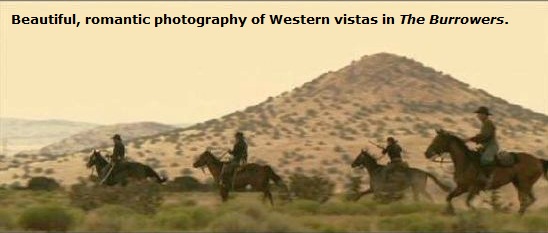

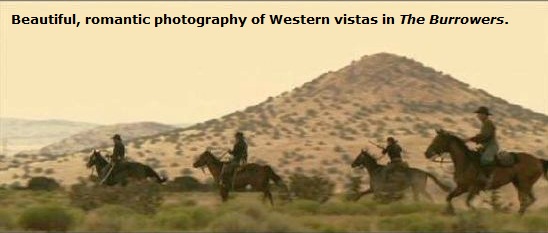

For the next 44-45 minutes,

The Burrowers is mostly a straight Western. Romantic

photography, charging horses, beautiful prairie vistas --

supported by appropriate Western period music.

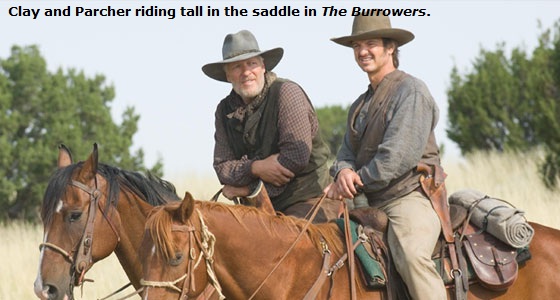

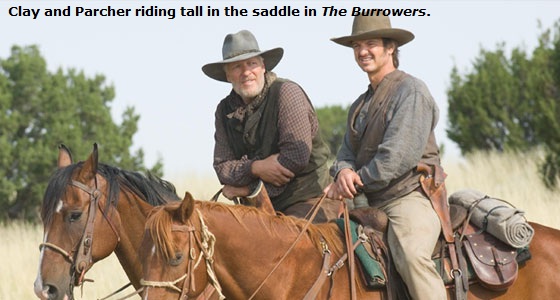

Psychologically, emotionally, dramatically, the characters are

typically Western. The strong and silent Clay (very much a

The Searchers, John Wayne type). The gentlemanly

gunslinger Mr. Parcher. Coffey, the romantic Irish immigrant,

riding to rescue Maryanne. Callaghan, the “noble Negro” (what

Spike Lee calls the "magical

Negro") -- compassionate, honorable, enduring racism

without ever losing his dignity.

There is also an arrogant U.S. Cavalry officer, callous and

cruel to both blacks and Indians. When he threatens to whip

Coffey for “feeding my Indian,” the strong and silent Clay

stares him down, ready for a gunfight, though outnumbered by

the officers' troops.

Naturally, the officer backs down from the heroic Clay.

Throughout these first 44-45 minutes, there are intimations

of horror -- the strange scars on a dead girl's neck;

strange holes in the ground; something in the bushes that

kills four troops. But overwhelmingly,

The Burrowers's mise-en-scène, music, story, characters,

and themes (loyalty toward loved ones and comrades; dignity in

the face of adversity) are those of a Western.

The film emotionally conditions the audience for

Western. Even if they know intellectually that they're

watching a horror film, they feel like they're watching

a Western. This conditions their expectations for a Western

outcome. They anticipate (even if only subconsciously) that

Coffey will rescue Maryanne. Most of the heroes will survive

-- and if any should die, they will die noble, honorable,

courageous deaths.

Yet as the film progresses,

The Burrowers morphs from a Western into a horror film.

Midway into the film, Clay is killed. It's not an honorable

death, but shocking and brutal. He dies not like John Wayne,

giving a noble speech while heroically fading away, but is

unceremoniously butchered like one of

Leatherface's victims.

Clay's death is emotionally jarring. I regard this as the

event that pushes the audience's mindset out of the Western

genre, and into horror.

Things worsen. The monsters (vampiric “burrowers” living

underground) reveal themselves. The

unnatural threat becomes clear and visible.

The burrowers' bite poisons Parcher. As he fades over the

course of the next day and night, he grows paranoid and

cowardly. He shoots at his former comrades, lest they desert

him.

In the end, he dies a coward's death. (His emotionally selfish

state of mind is not unlike the cowardly jock in

Jeepers Creepers 2 who wanted to abandon the weak ones,

only to be killed himself.)

Callaghan likewise dies a senseless, ignoble death, the

result of cowardice and incompetence. A victim of friendly

fire, and an incompetent army surgeon (who perhaps callously

amputated Callahan's leg, not much caring about a mere Negro's

health). Callaghan, the “noble Negro,” dies like a piece of

meat -- discarded like an anonymous victim in a slasher film.

Some friendly Indians die senseless deaths too, mistaken by

the army as hostiles and executed. Much like Ben was mistaken

for a zombie in

Night of the Living Dead, and thus killed by a sheriff's

posse. In horror films, innocents often die at the hands of

incompetent authority figures.

Coffey fails to rescue Maryanne, or anyone else. He fails to

bring proof of what he's learned about the burrowers. The

army, by killing the friendly Indians, kills any hope of

learning how to stop the burrowers. As in many horror films,

the protagonists stymie, but do not destroy, the threat.

Myers will return to kill again.

By starting as a straight Western (rather than a “horror

western”), and only morphing into horror after the audience

has been emotionally conditioned for a Western,

The Burrowers solves a common horror film problem:

Horror requires an

unnatural threat -- a sudden realization that (to quote

from Frank Lupo's

Werewolf pilot script) "The world is not as our minds

believe."

The problem is that audiences get jaded after seeing so many

horror films with the same

unnatural threat -- be it a vampires, zombies, or

uberpsychos. Familiarity breeds a sense of normalcy.

Seeing them so often, we come to feel that they're

commonplace, hence, natural.

As a result, horror filmmakers are challenged to find new ways

to "creep out" audiences with a novel

unnatural threat, some new threat that will

overturn viewers' sense of reality.

Because most horror filmmakers can't rise to the challenge,

they instead rely on gore and shocks (e.g.,

Devil's Grove).

The Burrowers solves this problem by starting as an

authentic Western. Only after the audience is

emotionally invested in a Western, with preconceived

expectations of the characters' heroic deeds and successful

fates, does the film emotionally jar them by segueing into a

horror film -- when the characters are suddenly revealed to be

cowardly and/or vulnerable.

Their deeds and deaths are typical for a horror film, but

shocking to an audience that had forgotten they were watching

a horror film.

Imagine

High Noon if, during the last third, Gary Cooper suddenly

turns cowardly, Grace Kelly is senselessly butchered like a

piece of meat, and half the town massacres the other half in

mindless mayhem.

The Burrowers demonstrates the emotional punch that comes

of establishing one genre in the audience's mind, then defying

their emotional expectations by morphing midway into

another genre. A non-horror sensibility is established,

into which any

unnatural threat feels that much more unnatural.

|

The “horror western” is a subgenre of the horror genre, not

the Western. The horror western uses Western icons

(e.g.,

The “horror western” is a subgenre of the horror genre, not

the Western. The horror western uses Western icons

(e.g.,